Willard Van Orman Quine

Willard Van Orman Quine |

|

| Full name | Willard Van Orman Quine |

|---|---|

| Born | June 25, 1908 Akron, Ohio |

| Died | December 25, 2000 (aged 92) Boston, Massachusetts |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Analytic |

| Main interests | Logic, Ontology, Epistemology, Philosophy of language, Philosophy of mathematics, Philosophy of science, Set theory. |

| Notable ideas | New Foundations, Indeterminacy of translation, Naturalized epistemology, Ontological relativity, Quine's paradox, Duhem-Quine thesis, Radical translation, Confirmation holism, Quine–McCluskey algorithm. |

|

Influenced by

|

|

Willard Van Orman Quine (June 25, 1908 – December 25, 2000) (known to intimates as "Van")[1] was an American philosopher and logician in the analytic tradition. From 1930 until his death 70 years later, Quine was continuously affiliated with Harvard University in one way or another, first as a student, then as a professor of philosophy and a teacher of mathematics, and finally as a professor emeritus who published or revised several books in retirement. He filled the Edgar Pierce Chair of Philosophy at Harvard from 1956 to 1978. A recent poll conducted among philosophers named Quine one of the five most important philosophers of the past two centuries.[2] He won the first Schock Prize in Logic and Philosophy in 1993, for "his systematical and penetrating discussions of how learning of language and communication are based on socially available evidence and of the consequences of this for theories on knowledge and linguistic meaning."[3]

Quine falls squarely into the analytic philosophy tradition while also being the main proponent of the view that philosophy is not merely conceptual analysis. His major writings include "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" (1951), which attacked the distinction between analytic and synthetic propositions and advocated a form of semantic holism, and Word and Object (1960), which further developed these positions and introduced the notorious indeterminacy of translation thesis. He also developed an influential naturalized epistemology that tried to provide "an improved scientific explanation of how we have developed elaborate scientific theories on the basis of meager sensory input."[4] He is also important in philosophy of science for his "systematic attempt to understand science from within the resources of science itself"[4] and for his conception of philosophy as continuous with science. This led to his famous quip that "philosophy of science is philosophy enough."[5] In philosophy of mathematics, he and his Harvard colleague Hilary Putnam developed the "Quine-Putnam indispensability thesis," an argument for the reality of mathematical entities.[6]

Contents |

Biography

According to his autobiography, The Time of My Life (1986), Quine grew up in Akron, Ohio where he lived with his parents and older brother Robert C. His father, Cloyd R., was a manufacturing entrepreneur and his mother, Harriett E. (also known as "Hattie" according to the 1920 census), was a schoolteacher and later a housewife.[1] He received his B.A. in mathematics and philosophy from Oberlin College in 1930 and his Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard University in 1932. His thesis supervisor was Alfred North Whitehead. He was then appointed a Harvard Junior Fellow, which excused him from having to teach for four years. During the academic year 1932–33, he travelled in Europe thanks to a Sheldon fellowship, meeting Polish logicians (including Alfred Tarski) and members of the Vienna Circle (including Rudolf Carnap).[1]

It was through Quine's good offices that Alfred Tarski was invited to attend the September 1939 Unity of Science Congress in Cambridge. To attend that Congress, Tarski sailed for the USA on the last ship to leave Gdańsk before the Third Reich invaded Poland. Tarski survived the war and worked another 44 years in the USA.

During World War II, Quine lectured on logic in Brazil, in Portuguese, and served in the United States Navy in a military intelligence role, deciphering messages from German submarines, and reaching the rank of Lieutenant Commander.[1]

At Harvard, Quine helped supervise the Harvard theses of, among others, Donald Davidson, David Lewis, Daniel Dennett, Gilbert Harman, Dagfinn Føllesdal, Hao Wang, Hugues LeBlanc and Henry Hiz. For the academic year 1964-1965, Quine was a Fellow on the faculty in the Center for Advanced Studies at Wesleyan University.[7]

Quine had four children by two marriages.[1] Guitarist Robert Quine was his nephew.

Political beliefs

Quine was politically conservative, but the bulk of his writing was in technical areas of philosophy removed from direct political issues.[8] He did, however, argue at points for several conservative positions: a defense of moral censorship;[9] and an argument against publicly funded education.[10][11]

Quine, like many philosophers in the Anglo-American "analytic" tradition, was critical of Jacques Derrida; in 1992, Quine led an unsuccessful petition to stop Cambridge University from granting Derrida an honorary degree. Such criticism was, according to Derrida, directed at Derrida "no doubt because [Derrida's methods, called] 'deconstructions', query or put into question a good many divisions and distinctions, for example the distinction between the pretended neutrality of philosophical discourse, on the one hand, and existential passions and drives on the other, between what is public and what is private, and so on."[12] Quine regarded Derrida's work as pseudophilosophy or sophistry.[13]

Work

Quine's Ph.D. thesis and early publications were on formal logic and set theory. Only after WWII did he, by virtue of seminal papers on ontology, epistemology and language, emerge as a major philosopher. By the 1960s, he had worked out his "naturalized epistemology" whose aim was to answer all substantive questions of knowledge and meaning using the methods and tools of the natural sciences. Quine roundly rejected the notion that there should be a "first philosophy", a theoretical standpoint somehow prior to natural science and capable of justifying it. These views are intrinsic to his naturalism.

Quine could lecture in French, Spanish, Portuguese and German, as well as his native English. But like the logical positivists, he evinced little interest in the philosophical canon: only once did he teach a course in the history of philosophy, on Hume. Quine has an Erdős number of 3.[14]

| Academic Genealogy | |

|---|---|

| Notable teachers | Notable students |

| Rudolf Carnap C. I. Lewis A. N. Whitehead |

Hilary Putnam Donald Davidson Daniel Dennett Dagfinn Føllesdal Gilbert Harman Saul Kripke David K. Lewis Thomas Nagel Hao Wang David Lyons Michael Slote Margaret Wilson Theodore Kaczynski Wolfgang Stegmüller Tom Lehrer Michael Silverstein |

Rejection of the analytic-synthetic distinction

In the 1930s and 40s, discussions with Rudolf Carnap, Nelson Goodman and Alfred Tarski, among others, led Quine to doubt the tenability of the distinction between "analytic" statements — those true simply by the meanings of their words, such as "All bachelors are unmarried" — and "synthetic" statements, those true or false by virtue of facts about the world, such as "There is a cat on the mat." This distinction was central to logical positivism. Although Quine is not normally associated with verificationism, some philosophers believe the tenet is not incompatible with his general philosophy of language, citing his Harvard colleague B.F. Skinner, and his analysis of language in Verbal Behavior.[15]

Like other Analytic philosophers before him, Quine accepted the definition of "analytic" as "true in virtue of meaning alone". Unlike them, however, he concluded that ultimately the definition was circular. In other words, Quine accepted that analytic statements are those that are true by definition, then argued that the notion of truth by definition was unsatisfactory.

Quine's chief objection to analyticity is with the notion of synonymy (sameness of meaning), a sentence being analytic, just in case it substitutes a synonym for one "black" in a proposition like "All black things are black" (or any other logical truth). The objection to synonymy hinges upon the problem of collateral information. We intuitively feel that there is a distinction between "All unmarried men are bachelors" and "There have been black dogs", but a competent English speaker will assent to both sentences under all conditions since such speakers also have access to collateral information bearing on the historical existence of black dogs. Quine maintains that there is no distinction between universally known collateral information and conceptual or analytic truths.

Another approach to Quine's objection to analyticity and synonymy emerges from the modal notion of logical possibility. A traditional Wittgensteinian view of meaning held that each meaningful sentence was associated with a region in the space of possible worlds. Quine finds the notion of such a space problematic, arguing that there is no distinction between those truths which are universally and confidently believed and those which are necessarily true.

Confirmation holism and ontological relativity

The central theses underlying the indeterminacy of translation and other extensions of Quine's work are ontological relativity and the related doctrine of confirmation holism. The premise of confirmation holism is that all theories (and the propositions derived from them) are under-determined by empirical data (data, sensory-data, evidence); although some theories are not justifiable, failing to fit with the data or being unworkably complex, there are many equally justifiable alternatives. While the Greeks' assumption that (unobservable) Homeric gods exist is false, and our supposition of (unobservable) electromagnetic waves is true, both are to be justified solely by their ability to explain our observations.

Quine concluded his "Two Dogmas of Empiricism" as follows:

As an empiricist I continue to think of the conceptual scheme of science as a tool, ultimately, for predicting future experience in the light of past experience. Physical objects are conceptually imported into the situation as convenient intermediaries not by definition in terms of experience, but simply as irreducible posits comparable, epistemologically, to the gods of Homer . . . For my part I do, qua lay physicist, believe in physical objects and not in Homer's gods; and I consider it a scientific error to believe otherwise. But in point of epistemological footing, the physical objects and the gods differ only in degree and not in kind. Both sorts of entities enter our conceptions only as cultural posits.

Quine's ontological relativism (evident in the passage above) led him to agree with Pierre Duhem that for any collection of empirical evidence, there would always be many theories able to account for it. However, Duhem's holism is much more restricted and limited than Quine's. For Duhem, underdetermination applies only to physics or possibly to natural science, while for Quine it applies to all of human knowledge. Thus, while it is possible to verify or falsify whole theories, it is not possible to verify or falsify individual statements. Almost any particular statements can be saved, given sufficiently radical modifications of the containing theory. For Quine, scientific thought forms a coherent web in which any part could be altered in the light of empirical evidence, and in which no empirical evidence could force the revision of a given part.

Quine's writings have led to the wide acceptance of instrumentalism in the philosophy of science.

Existence and Its Contrary

The problem of non-referring names is an old puzzle in philosophy, which Quine captured eloquently when he wrote,

- "A curious thing about the ontological problem is its simplicity. It can be put into three Anglo-Saxon monosyllables: 'What is there?' It can be answered, moreover, in a word—'Everything'—and everyone will accept this answer as true."[16]

More directly, the controversy goes,

- "How can we talk about Pegasus? To what does the word 'Pegasus' refer? If our answer is, 'Something,' then we seem to believe in mystical entities; if our answer is, 'nothing', then we seem to talk about nothing and what sense can be made of this? Certainly when we said that Pegasus was a mythological winged horse we make sense, and moreover we speak the truth! If we speak the truth, this must be truth about something. So we cannot be speaking of nothing."

Quine resists the temptation to say that non-referring terms are meaningless for reasons made clear above. Instead he tells us that we must first determine whether our terms refer or not before we know the proper way to understand them. However, Czesław Lejewski criticizes this belief for reducing the matter to empirical discovery when it seems we should have a formal distinction between referring and non-referring terms or elements of our domain. Lejewski writes further,

- "This state of affairs does not seem to be very satisfactory. The idea that some of our rules of inference should depend on empirical information, which may not be forthcoming, is so foreign to the character of logical inquiry that a thorough re-examination of the two inferences [existential generalization and universal instantiation] may prove worth our while."

Lejewski then goes on to offer a description of free logic, which he claims accommodates an answer to the problem.

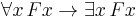

Lejewski also points out that free logic additionally can handle the problem of the empty set for statements like  . Quine had considered the problem of the empty set unrealistic, which left Lejewski unsatisfied.[17]

. Quine had considered the problem of the empty set unrealistic, which left Lejewski unsatisfied.[17]

Logic

Over the course of his career, Quine published numerous technical and expository papers on formal logic, some of which are reprinted in his Selected Logic Papers and in The Ways of Paradox.

Quine confined logic to classical bivalent first-order logic, hence to truth and falsity under any (nonempty) universe of discourse. Hence the following were not logic for Quine:

- Higher order logic and set theory. He famously referred to higher order logic as "set theory in disguise";

- Much of what Principia Mathematica included in logic was not logic for Quine.

- Formal systems involving intensional notions, especially modality. Quine was especially hostile to modal logic with quantification, a battle he largely lost when Saul Kripke's relational semantics became canonical for modal logics.

Quine wrote three undergraduate texts on logic:

- Elementary Logic. While teaching an introductory course in 1940, Quine discovered that extant texts for philosophy students did not do justice to quantification theory or first-order predicate logic. Quine wrote this book in 6 weeks as an ad hoc solution to his teaching needs.

- Methods of Logic. The four editions of this book resulted from a more advanced undergraduate course in logic Quine taught from the end of WWII until his 1978 retirement.

- Philosophy of Logic. A concise and witty undergraduate treatment of a number of Quinian themes, such as the prevalence of use-mention confusions, the dubiousness of quantified modal logic, and the non-logical character of higher-order logic.

Mathematical Logic is based on Quine's graduate teaching during the 1930s and 40s. It shows that much of what Principia Mathematica took more than 1000 pages to say can be said in 250 pages. The proofs are concise, even cryptic. The last chapter, on Gödel's incompleteness theorem and Tarski's indefinability theorem, along with the article Quine (1946), became a launching point for Raymond Smullyan's later lucid exposition of these and related results.

Quine's work in logic gradually became dated in some respects. Techniques he did not teach and discuss include analytic tableaux, recursive functions, and model theory. His treatment of metalogic left something to be desired. For example, Mathematical Logic does not include any proofs of soundness and completeness. Early in his career, the notation of his writings on logic was often idiosyncratic. His later writings nearly always employed the now-dated notation of Principia Mathematica. Set against all this are the simplicity of his preferred method (as exposited in his Methods of Logic) for determining the satisfiability of quantified formulas, the richness of his philosophical and linguistic insights, and the fine prose in which he expressed them.

Most of Quine's original work in formal logic from 1960 onwards was on variants of his predicate functor logic, one of several ways that have been proposed for doing logic without quantifiers. For a comprehensive treatment of predicate functor logic and its history, see Quine (1976). For an introduction, see chpt. 45 of his Methods of Logic.

Quine was very warm to the possibility that formal logic would eventually be applied outside of philosophy and mathematics. He wrote several papers on the sort of Boolean algebra employed in electrical engineering, and with Edward J. McCluskey, devised the Quine–McCluskey algorithm of reducing Boolean equations to a minimum covering sum of prime implicants.

Set theory

While his contributions to logic include elegant expositions and a number of technical results, it is in set theory that Quine was most innovative. He always maintained that mathematics required set theory and that set theory was quite distinct from logic. He flirted with Nelson Goodman's nominalism for a while, but backed away when he failed to find a nominalist grounding of mathematics.

Over the course of his career, Quine proposed three variants of axiomatic set theory, each including the axiom of extensionality:

- New Foundations, NF, creates and manipulates sets using a single axiom schema for set admissibility, namely an axiom schema of stratified comprehension, whereby all individuals satisfying a stratified formula compose a set. A stratified formula is one that type theory would allow, were the ontology to include types. However, Quine's set theory does not feature types. The metamathematics of NF are curious. NF allows many "large" sets the now-canonical ZFC set theory does not allow, even sets for which the axiom of choice does not hold. Since the axiom of choice holds for all finite sets, the failure of this axiom in NF proves that NF includes infinite sets. The (relative) consistency of NF is an open question. A modification of NF, NFU, due to R. B. Jensen and admitting urelements (entities that can be members of sets but that lack elements), turns out to be consistent relative to Peano arithmetic, thus vindicating the intuition behind NF. NF and NFU are the only Quinian set theories with a following. For a derivation of foundational mathematics in NF, see Rosser (1953);

- The set theory of Mathematical Logic is NF augmented by the proper classes of Von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel set theory, except axiomatized in a much simpler way;

- The set theory of Set Theory and Its Logic does away with stratification and is almost entirely derived from a single axiom schema. Quine derived the foundations of mathematics once again. This book includes the definitive exposition of Quine's theory of virtual sets and relations, and surveyed axiomatic set theory as it stood circa 1960. However, Fraenkel, Bar-Hillel and Levy (1973) do a better job of surveying set theory as it stood at mid-century.

All three set theories admit a universal class, but since they are free of any hierarchy of types, they have no need for a distinct universal class at each type level.

Quine's set theory and its background logic were driven by a desire to minimize posits; each innovation is pushed as far as it can be pushed before further innovations are introduced. For Quine, there is but one connective, the Sheffer stroke, and one quantifier, the universal quantifier. All polyadic predicates can be reduced to one dyadic predicate, interpretable as set membership. His rules of proof were limited to modus ponens and substitution. He preferred conjunction to either disjunction or the conditional, because conjunction has the least semantic ambiguity. He was delighted to discover early in his career that all of first order logic and set theory could be grounded in a mere two primitive notions: set abstraction and inclusion. For an elegant introduction to the parsimony of Quine's approach to logic, see his "New Foundations for Mathematical Logic," ch. 5 in his From a Logical Point of View.

Quine's epistemology

Just as he challenged the dominant analytic-synthetic distinction, Quine also took aim at traditional normative epistemology. According to Quine, normative epistemology is the trend that assigns ought claims to conditions of knowledge. This approach, he argued, has failed to give us any real understanding of the necessary and sufficient conditions for knowledge. Quine recommended that, as an alternative, we look to natural sciences like psychology for a full explanation of knowledge. Thus, we must totally replace our entire epistemological paradigm. Quine's proposal is extremely controversial among contemporary philosophers and has several important critics, with Jaegwon Kim the most prominent among them.[18]

In popular culture

- A computer program whose output is its source code is named a "quine" after W.V. Quine.

Bibliography

Selected books

- 1951 (1940). Mathematical Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-55451-5.

- 1966. Selected Logic Papers. New York: Random House.

- 1970 (2nd ed., 1978). With J. S. Ullian. The Web of Belief. New York: Random House.

- 1980 (1941). Elementary Logic. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-24451-6.

- 1982 (1950). Methods of Logic. Harvard Univ. Press.

- 1980 (1953). From a Logical Point of View. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-674-32351-3. Contains "Two dogmas of Empiricism."

- 1960 Word and Object. MIT Press; ISBN 0-262-67001-1. The closest thing Quine wrote to a philosophical treatise. Chpt. 2 sets out the indeterminacy of translation thesis.

- 1974 (1971) The Roots of Reference. Open Court Publishing Company ISBN 0-8126-9101-6 (developed from Quine's Carus Lectures)

- 1976 (1966). The Ways of Paradox. Harvard Univ. Press.

- 1969 Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. Columbia Univ. Press. ISBN 0-231-08357-2. Contains chapters on ontological relativity, naturalized epistemology and natural kinds.

- 1969 (1963). Set Theory and Its Logic. Harvard Univ. Press.

- 1985 The Time of My Life – An Autobiography. Cambridge, The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-17003-5. 1986: Harvard Univ. Press.

- 1986 (1970). The Philosophy of Logic. Harvard Univ. Press.

- 1987 Quiddities: An Intermittently Philosophical Dictionary. Harvard Univ. Press. ISBN 0-14-012522-1. A work of essays, many subtly humorous, for lay readers, very revealing of the breadth of his interests.

- 1992 (1990). Pursuit of Truth. Harvard Univ. Press. A short, lively synthesis of his thought for advanced students and general readers not fooled by its simplicity. ISBN 0-674-73951-5.

Important articles

- 1946, "Concatenation as a basis for arithmetic." Reprinted in his Selected Logic Papers. Harvard Univ. Press.

- 1948, "On What There Is", Review of Metaphysics. Reprinted in his 1953 From a Logical Point of View. Harvard University Press.

- 1951, "Two Dogmas of Empiricism", The Philosophical Review 60: 20–43. Reprinted in his 1953 From a Logical Point of View. Harvard University Press.

- 1956, "Quantifiers and Propositional Attitudes," Journal of Philosophy 53. Reprinted in his 1976 Ways of Paradox. Harvard Univ. Press: 185–96.

- 1969, "Epistemology Naturalized" in Ontological Relativity and Other Essays. New York: Columbia University Press: 69–90.

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. (October 2003), "Willard Van Orman Quine", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Quine.html.

- ^ "So who *is* the most important philosopher of the past 200 years?" Leiter Reports. Leiterreports.typepad.com. 11 March 2009. Accessed 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Prize winner page". The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Kva.se. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ a b "Quine's Philosophy of Science". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Iep.utm.edu. 27 July 2009. Accessed 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Mr Strawson on Logical Theory". WV Quine. Mind Vol. 62 No. 248. Oct. 1953.

- ^ Colyvan, Mark, "Indispensability Arguments in the Philosophy of Mathematics", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2004 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.)

- ^ "Guide to the Center for Advanced Studies Records, 1958 - 1969". Weselyan University. Wesleyan.edu. Accessed 8 March 2010.

- ^ Wall Street Journal obituary for W V Quine - Jan 4 2001

- ^ Quiddities: An Intermittently Philosophical Dictionary, entries for Tolerance (pp.206-8) and Freedom (p.69)

- ^ “Paradoxes of Plenty” in Theories and Things p.197

- ^ The Time of My Life: An Autobiography, pp. 352-3

- ^ The 'Derrida Affair' at Cambridge University, from "Honoris Causa" pp. 409-413

- ^ J.E. D'Ulisse Derrida (1930-2004), New Partisan 12.24.2004

- ^ "MR: Collaboration Distance". American Mathematical Society. Ams.org. Retrieved 29 August 2010.

- ^ Prawitz, Dag. 'Quine and Verificationism.' In Inquiry, Stockholm, 1994, p 487 - 494

- ^ W.V.O. Quine, "On What There Is" The Review of Metaphysics, New Haven 1948, 2, 21

- ^ Czeslaw Lejewski, "Logic and Existence" British Journal for the Philosophy of Science Vol. 5 (1954–5), pp. 104–119

- ^ "Naturalized Epistemology". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Plato.stanford.edu. 5 July 2001. Accessed 8 March 2010.

Further reading

- Gibson, Roger F., 1982/86. The Philosophy of W.V. Quine: An Expository Essay. Tampa: University of South Florida.

- ————, 1988. Enlightened Empiricism: An Examination of W. V. Quine's Theory of Knowledge Tampa: University of South Florida.

- ————, ed., 2004. The Cambridge Companion to Quine. Cambridge University Press.

- ————, 2004. Quintessence: Basic Readings from the Philosophy of W. V. Quine. Harvard Univ. Press.

- ———— and Barrett, R., eds., 1990. Perspectives on Quine. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Gochet, Paul, 1978. Quine en perspective, Paris, Flammarion.

- Godfrey-Smith, Peter, 2003. Theory and Reality: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Science.

- Grattan-Guinness, Ivor, 2000. The Search for Mathematical Roots 1870–1940. Princeton University Press.

- Grice, Paul and Peter Strawson. "In Defense of a Dogma". The Philosophical Review 65 (1965).

- Hahn, L. E., and Schilpp, P. A., eds., 1986. The Philosophy of W. V. O. Quine (The Library of Living Philosophers). Open Court.

- Köhler, Dieter, 1999/2003. Sinnesreize, Sprache und Erfahrung: eine Studie zur Quineschen Erkenntnistheorie. Ph.D. thesis, Univ. of Heidelberg.

- Orenstein, Alex (2002). W.V. Quine. Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, Hilary. "The Greatest Logical Positivist." Reprinted in Realism with a Human Face, ed. James Conant. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990.

- Rosser, John Barkley, 1953.

- Valore, Paolo, 2001. Questioni di ontologia quineana, Milano: Cusi.

External links

- Willard Van Orman Quine—Philosopher and Mathematician

- Willard Van Orman Quine at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Quine's Philosophy of Science at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Quine's New Foundations at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Willard Van Orman Quine at the Mathematics Genealogy Project.

- Obituary from The Guardian

- "Two Dogmas of Empiricism"

- "On Simple Theories Of A Complex World"

- What is Quine's Ontology?